Why Do We Sleep and What’s the Deal with Dreams?

Sleep and dreams represent fundamental and enigmatic aspects of human existence. Scientific exploration has shed light on the biology and psychology underlying these phenomena. While sleep serves to optimize cognitive functions such as memory consolidation, concentration, and emotional regulation, dreams play a role in processing emotions, managing traumatic experiences, and enhancing creativity.

Throughout history, various cultures have interpreted dreams in diverse ways. In ancient Egypt, dreams were regarded as sources of prophecy and inspiration, with pharaohs seeking guidance from dream interpreters before making important decisions. Similarly, ancient Greeks viewed dreams as messages from the gods, while Hippocrates proposed that dreams could aid in diagnosing illnesses.

Modern science views dreams as products of the brain. The 19th century saw the exploration of brain waves, leading to the identification of distinct sleep stages. Sigmund Freud, in the 20th century, posited that dreams offer a glimpse into the subconscious mind.

Research on dreams accelerated with the understanding of sleep cycles and the advent of tools like the electroencephalogram (EEG), which measures brain activity via electrodes on the scalp. The discovery of REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep in 1953 marked a significant milestone, revealing that individuals consistently recall dreams when awakened during this stage, occurring approximately every ninety minutes.

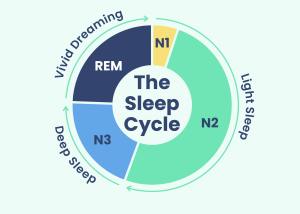

Sleep is a resting state marked by reduced conscious awareness and decreased responsiveness. Brain wave patterns shift in frequency and amplitude, while muscle activity decreases. It comprises two primary stages: NREM (Non-Rapid Eye Movement) and REM (Rapid Eye Movement), with NREM sleep further divided into three stages: N1, N2, and N3.

N1: This initial stage heralds the onset of sleep. Brain waves slow, and muscle activity diminishes. As we prepare to slip into slumber, our brain activity begins to decelerate, characterised by alpha waves—synchronised waves associated with relaxation. These waves peak in intensity as we close our eyes, gradually diminishing until we drift into unconsciousness.

N1: This initial stage heralds the onset of sleep. Brain waves slow, and muscle activity diminishes. As we prepare to slip into slumber, our brain activity begins to decelerate, characterised by alpha waves—synchronised waves associated with relaxation. These waves peak in intensity as we close our eyes, gradually diminishing until we drift into unconsciousness.

N2: Sleep deepens, with further slowing of brain waves, accompanied by a decrease in heart rate and respiration. Notably, this stage hosts the intriguing phenomenon of dreaming or hypnagogic reverie. As sleep deepens, these reveries evolve into vivid visions or imagery, transitioning from simple mental exercises like counting sheep to more immersive experiences.

N3: This phase encompasses deep sleep, marked by a significant slowdown in brain waves and pronounced reduction in muscle activity. Here, the body releases growth hormone and alleviates fatigue. Subsequently, the brain exhibits slow or delta waves, reflecting diminished mental activity. Occasionally, this stage may trigger responses indicative of a state of emergency.

REM sleep represents the pinnacle of sleep depth, characterised by brain waves resembling wakefulness and accompanied by rapid eye movements beneath closed eyelids. Typically, dreams occur during REM sleep.

In a chronological context, if sleep onset occurs at 11:00 PM, the initial REM period would occur around 1:00 AM, followed by subsequent REM periods, increasing in duration. Towards the later hours of the morning, REM phases may extend up to 40 minutes, facilitating more intricate dream experiences.

The discovery that the brain is as active during REM sleep as it is during wakefulness, as revealed by EEG, was surprising. In a study published in the Annual Review of Psychology in 1973, the authors stated: ” As data develop on the phenomenology of sleep states, it becomes increasingly clear that sleep is not simply a resting state, waxing and waning near the lower pole of a continuum of vigilance. Instead, sleep appears to be an extremely complex, constantly changing, but cyclic succession of psychophysiological patterns, qualitatively rather than quantitatively different from those of waking.”

Why do we dream?

Though the precise purpose of dreams remains elusive, scientific investigation presents several potential roles that dreams may fulfil for the brain.

Memory consolidation: One proposed function suggests that dreams are integral to reinforcing memory and emotional learning. During sleep, the brain undergoes a process of fortifying significant memories and emotional experiences. Dreams can act as a replay of these crucial memories, facilitating the strengthening of neural connections. Conversely, the neural connections associated with less important memories may weaken. This notion finds support in research demonstrating enhanced memory and recall following REM sleep.

Emotional processing and stress management: Dreams may serve as a mechanism for emotional release, enabling individuals to grapple with complex feelings and anxieties within a safe realm. The theory of emotional regulation posits that dreams offer a platform for processing challenging or unresolved emotions. By confronting these emotions through dreams, individuals may gain deeper insight and achieve a more balanced emotional state upon awakening.

Mental rehearsal: Some researchers propose that dreams provide a space for mental rehearsal, allowing individuals to review past experiences or simulate potential scenarios. By mentally rehearsing emotional responses, coping strategies, and problem-solving techniques, individuals may enhance their readiness to tackle similar situations in real life.

Creativity and problem-solving: An alternative perspective suggests that dreams foster creativity and nurture problem-solving abilities. The content of dreams has been linked to an individual’s creative thinking prowess, potentially aiding in the resolution of complex issues or the generation of innovative ideas.

Each of these theories offers valuable insights into the potential functions of dreams. However, definitive answers regarding the nature and purpose of dreams remain elusive, driving ongoing research into this intriguing subject.

Newer hypotheses suggest that dreams may also be necessary to maintain brain functions during sleep. It is likely that the function of dreams consists of a complex interaction of these functions and plays a multifaceted role in maintaining our cognitive and emotional health.

Lucid Dreams

Lucid dreams occur when you are aware that you are dreaming and can actively control the dream environment and its characters. During these dreams, the normally dormant frontal lobe of your brain, responsible for decision-making and self-awareness, becomes active. This heightened brain activity allows you to maintain awareness of the dream state and exert influence over its content.

Scientific studies validating the existence of lucid dreaming have provided a new avenue for dream research, albeit one fraught with inherent challenges due to the elusive nature of dreams.

Brain scans conducted on individuals experiencing lucid dreams reveal patterns akin to wakefulness. In experiments involving lucid dreamers, researchers observed consistent brain activity across various states, including dreaming, wakefulness with open eyes, and daydreaming with closed eyes while consciously performing repetitive movements. This suggests that conscious awareness can indeed be sustained during the dream state.

Furthermore, studies have demonstrated sustained activity in key brain regions during lucid dreaming, including the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, and temporal lobe. These areas are crucial for functions such as consciousness, attention, memory, and emotional processing, indicating that lucid dreaming involves complex cognitive processes beyond mere passive dreaming.

Sleeping and Dreams in Animals

Observations of young jumping spiders have revealed that their retinas continue to move while they sleep at night, resembling the Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep phase in humans. Researchers have identified these spider behaviors as akin to short periods of REM sleep, yet it remains uncertain whether spiders truly enter a state of sleep during these episodes. If indeed asleep and exhibiting REM-like behaviors, it raises the intriguing possibility that spiders may dream. This discovery suggests that REM sleep might be more widespread in the animal kingdom than previously assumed, hinting at its potential significance across various species. Nevertheless, some scientists remain sceptical about whether the observed behaviors accurately correspond to REM sleep, highlighting the lack of a reliable method to ascertain whether animals dream.

The evolutionary origins and functions of REM sleep remain largely elusive. Researchers seek to illuminate this aspect by examining brain activity in spiders, alongside similar REM-like behaviors observed in other animal species. However, the correlation between these behaviors and dreaming remains ambiguous. While the existence of REM-like cycles in the animal kingdom hints at a potential link to dreaming, conclusive evidence remains elusive.

Sleep and dreams are enigmatic yet pervasive experiences shared by humans and animals alike. Scientists strive daily to unravel the intricacies of these phenomena, recognising their vital roles in both bodily and cognitive functions. Dreams, intertwined with memory, emotions, and learning, add another layer of complexity to the sleep cycle. The diverse sleep and dream patterns observed across different species fuel curiosity and drive future research efforts. Through ongoing studies, we anticipate gaining deeper insights into the biological and psychological mechanisms of sleep and dreams, unveiling their significance across diverse species.

REFERENCES

- 1. https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev.ps.24.020173.001431

- 2. https://thefulcrum.ca/sciencetech/the-science-of-sleep/

- 3. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/do-other-animals-dream-180982861/

- 4. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41593-023-01449-7#Sec2

- 5. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.2466/pms.1981.52.3.727

- 6. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/lucid-dream-sleep-mind-neuroscience-brain

- 7. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-do-we-dream-maybe-to-ensure-we-can-literally-see-the-world-upon-awakening/