The Past, Present, and Future of Space Stations

When the International Space Station (ISS) will be out of service in 2030, cosmic laboratories in low Earth orbit will not remain empty.

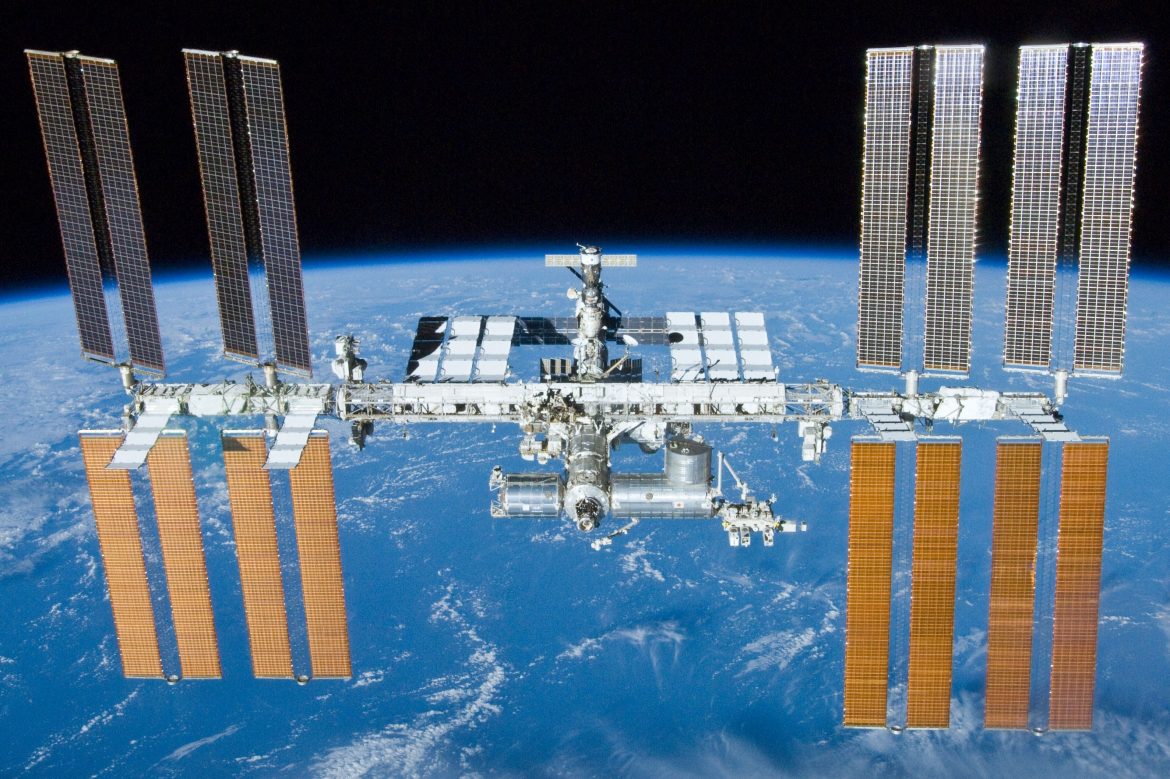

The International Space Station (ISS) has been in orbit for more than 20 years and is one of the most expensive man-made structures ever built, costing NASA about 4 billion dollars a year. This is why NASA is planning to open the Space Station for commercial operation in order to allocate its budget elsewhere. Also, due to the recent drop in prices to launch any cargo into orbit, companies can now build and operate their own space stations.

Besides its cost, there is also the hard fact that the ISS cannot operate forever. While the demand for Low Earth Orbit (LEO) access continues to grow, NASA plans to support several commercial space stations to replace the ISS.

In addition to these, China’s efforts to establish its own independent space station continues, and Russia has departed from the ISS followed by the announcement of their aim to build a new space station.

Let’s take a brief look at the history and future of space stations.

The First Stations

The initial stations had monolithic designs, usually built as a single piece containing all materials and experimental equipment, and sent into space by a single carrier rocket. A team could then be sent to man the station and conduct research. Once the supplies ran out, the stations were abandoned.

The first space station was Salyut 1, launched by the Soviet Union on April 19, 1971. All of the first Soviet space stations were called “Salyut”, but they came in two different types: civilian and military. Military stations Salyut 2, Salyut 3, and Salyut 5 were also known as Almaz stations.

Salyut 6 and Salyut 7 were civilian stations, equipped with two docking gates that allowed a second crew to arrive in a new spacecraft. The Soyuz craft was able to spend 90 days in space, after which it had to be replaced by a new spacecraft. This allowed a crew to continuously manage the station.

American Skylab (1973–1979) was also equipped with two docking gates, just like the second generation stations, although the extra gate was never used. The presence of a second gate at the new stations allowed Progress supply vehicles to dock at the station, which made it possible to bring in new supplies to aid long-duration missions.

Modular Stations

Unlike previous stations, the Soviet space station Mir had a modular design; following the launch of a core module (or base block), additional modules that often had specific roles could be added to it. Its assembly in orbit took 10 years, from 1986 to 1996.

This modular structure provides greater operational flexibility while eliminating the need for a single, extremely powerful launch vehicle. Modular stations are also designed ab initio to accommodate logistics support vehicles that provide consumables, which ensures a longer lifespan, albeit at the expense of regular support launches.

Mir was the first long-term research station in orbit that was continuously inhabited, and held the record for the longest continuous human presence in space at 3,644 days, until ISS broke this record on October 23, 2010. The spaceflight of Valeri Polyakov, in which he spent 437 days and 18 hours on the station during 1994-1995, is still the longest single-manned space mission. Capable of constantly supporting an on-board crew of three, with the ability to host a more crowded team during shorter missions, Mir was occupied for 12.5 years of its 15-year life.

The ISS has two main segments; the Russian Orbital Segment (ROS) and the US Orbital Segment (USOS). The first module of the ISS, Zarya, was launched in 1998. The “second generation” modules of the ROS could be launched with Proton rockets, fly right to the correct orbit and deploy themselves without human intervention. The necessary connections for power, data, gases and propellants can be made automatically.

Although the second-generation Russian modules can be reused, Roscosmos has announced that they are not planning to separate these modules from the ISS when they end their partnership with the ISS in 2024.

In contrast, the main US modules of ISS were launched on the Space Shuttle and attached to the station by astronauts during extravehicular activities (EVAs), when connections for power, data, propulsion and cooling fluids were also made. As these modules were integrated as a single block, it cannot be disassembled when it is necessary to deorbit the station. When the ISS completes its mission (currently planned to happen in 2030), it will be deorbited and crashed into the Earth’s surface in a controlled manner.

Space laboratory Tiangong-1, the first of two structures launched into orbit as a precursor to China’s space station project, entered orbit in September 2011. The unmanned Shenzhou 8 successfully performed an automated rendezvous and docking in November 2011. Afterward, two separate manned missions visited Tiangong-1. In 2013, this laboratory completed its mission by falling into the Pacific Ocean.

Similarly, Tiangong-2 served in orbit between 2016 and 2019 and was burned in the atmosphere during deorbiting.

The Future of Space Stations

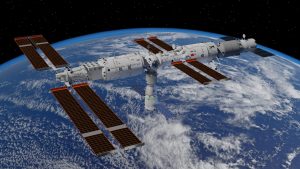

TIANGONG

Although only partially built, for now, the two-module (soon to be three) Tiangong space station has a big role to play in China’s overall goals in space.

Compared to the six-module ISS, China’s orbiting platforms are modest. Tiangong, whose third and main module is scheduled for launch in October 2022, will also be equipped with a robotic arm like the ISS. This will give Tiangong the ability to support Xuntian, the first space telescope China plans to put into orbit within the next two or three years. Xuntian will fly in low Earth orbit and will have more in common with the Hubble Space Telescope than the James Webb Space Telescope. However, its field of view will be 300 times larger than Hubble’s.

The Chinese Space Agency plans to conduct experiments aboard Tiangong in several fields including physics, life and biotechnology, fluid physics in microgravity, and materials science.

ISS and AXIOM

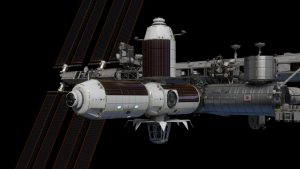

It is already known that NASA wishes to open the ISS to commercial use once Russia departs from the mission, and a private company called Axiom Space has taken this opportunity to build their planned space station. Axiom’s plan is to build the future space station by first attaching it to the ISS, to later detach once all modules are connected, to become an independent space station.

The fully assembled Axiom Station will nearly double the usable volume of the ISS. The first module is scheduled to be attached to the ISS in 2024 and completed in 2028. The Axiom Station will be used for research in microgravity and space manufacturing.

ORBITAL REEF

Towards the end of 2020’s, a commercially developed and operated space station will begin orbiting the Earth as a mixed-use business park with direct access for everyone. Orbital Reef will be a private space station built for commerce, tourism, and research, able to support a crew of 10. This project entails the collaboration of a group of private space companies. Led by Blue Origin and Sierra Space, this group includes Boeing and the University of Arizona, among other companies.

STARLAB

Starlab’s main structure will consist of a large inflatable habitat and a metallic docking point. The regenerative ECLSS (environmental control and life support system) will ensure the constant availability of a crew of four to live and work in a large volume of 340 cubic metres. The station will also have a 60kW power and propulsion element, a large robotic arm to serve cargo and external payloads, and an advanced research laboratory system.

The George Washington Science Park, of which Starlab is its heart, has four main operational divisions: a biology laboratory, a plant laboratory, a laboratory for physics and materials research, and an open workspace. Nanoracks, the operator of the space station, and a team of experts are planning the Science Park to meet the needs of researchers and commercial customers. We should also note that the living spaces for astronauts will be designed by Hilton.

LUNAR GATEWAY

The most anticipated space station of the near future is possibly the Lunar Gateway, part of the Artemis mission that aims to put humans back on the Moon to start a permanent settlement on the lunar surface.

The Artemis project is predominantly led by NASA, with contributions from several other space agencies including the European Space Agency (ESA), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).

Lunar Gateway will orbit the Moon and serve as a staging point for both robotic and manned exploration of the lunar south pole. It is also the proposed staging point for NASA’s Deep Space concept for going to Mars. The station is currently scheduled for launch in November 2024, and will be able to support a crew of four.

REFERENCES

- 1. https://rocketcrew.space/blog/future-space-stations

- 2. https://spacenews.com/blue-origin-and-sierra-space-announce-plans-for-commercial-space-station/

- 3. https://spacenews.com/nanoracks-and-lockheed-martin-partner-on-commercial-space-station-project/

- 4. https://www.popsci.com/science/tiangong-chinese-space-station/ https://www.sciencefocus.com/space/nasa-lunar-gateway/